OpenClaw has 34,600 forks.

Yesterday, its creator joined OpenAI.

These two facts are related in ways that are worth pulling apart.

What 34,600 forks actually looks like

A GitHub fork costs nothing — one click, two seconds. It’s a bookmark with delusions of contribution. So I pulled the data from GitHub’s API to see what’s actually going on underneath the vanity number.

GitHub’s API for listing forks returns a maximum of 400 results per request. You can sort by oldest or newest, so you get the first 400 forks ever created and the 400 most recent ones. The ~33,000 forks in between? Invisible. GitHub literally won’t show them to you. You’d need to scrape each fork individually or use their BigQuery dataset to see the full picture. I didn’t — so this analysis covers the bookends with a black hole in the middle. I’m not going to dress it up.

The growth curve

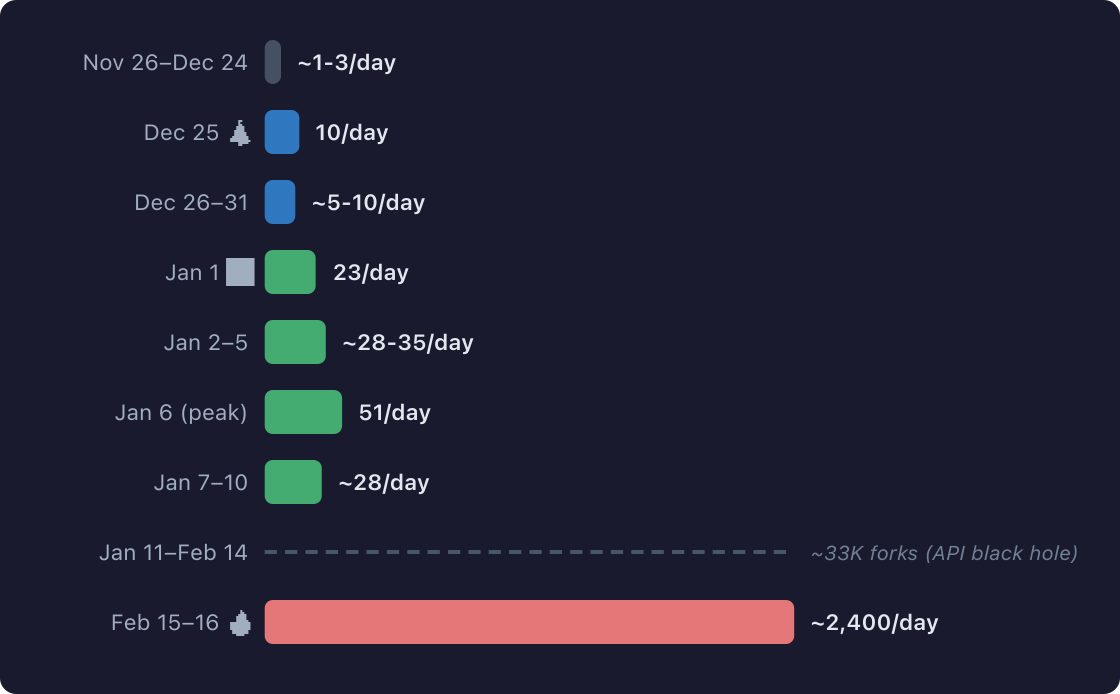

The first fork appeared November 26, 2025 — two days after the repo went public. For the next month: a trickle. One, two, three forks per day. Early adopters kicking the tires.

Then Christmas happened.

December 25: 10 forks. A 10x jump. People unwrapped laptops and had free time. The holiday week held steady at 5-10 per day.

January 1: 23 forks. Another 3x. By January 6, it peaked at 51 forks/day in the sample. New Year’s resolution energy: “this is the year I set up my own AI agent.”

And right now? ~100 forks per hour. 345 forks appeared in a 4.3-hour window. That’s a ~2,400/day pace.

The trajectory: 1/day → 10/day → 50/day → 100/hour.

Somewhere between people opening Christmas presents and Valentine’s Day, OpenClaw went from “interesting open-source tool” to “phenomenon.” Which is a convenient time for the phenomenon’s creator to get hired by the company that didn’t make it.

The 81% question

Here’s the part nobody talks about.

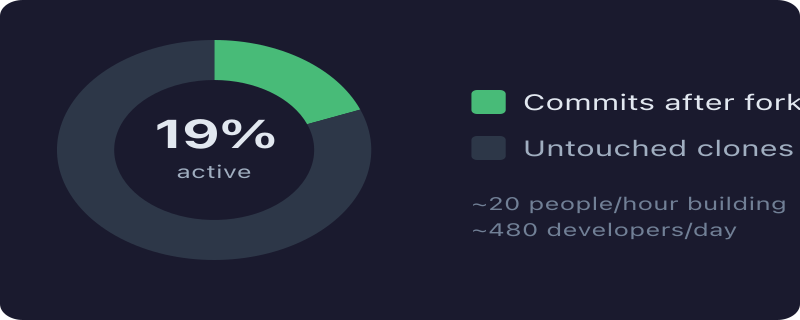

Of the 100 most recent forks — all created within the last hour of my sample — how many show any commit activity after forking?

19%.

The other 81% are untouched clones. Fork and forget. GitHub stars with extra steps.

But before you dismiss it: 19% of 100 forks per hour is still ~20 people per hour actually building something. That’s ~480 developers per day doing real work on top of OpenClaw. Not nothing. Especially for a project that, until yesterday, was one developer’s playground.

The ones who renamed their fork (and are apparently walking away from Omelas)

The most interesting signal isn’t volume — it’s intent. When someone renames their fork, they’re not cloning; they’re starting something new.

Highlights:

cl-core-mit-snapshot— someone freezing the codebase under MIT. Defensive forking. Just in case.openclaw-x402-router— x402 payment protocol integration. Somebody’s building monetized agent infrastructure before the foundation even has bylaws.reallyopenopenclaw— a philosophical statement in repo form. Already preemptively arguing with the future.ladysclaw— rebranding energy.clawguard— presumably security hardening.shoelace— no explanation. Just vibes.

These are the 2% who forked with purpose. Watch them.

People aren’t just watching

OpenClaw’s stars-to-forks ratio is 5.7:1 (197K stars to 34.6K forks). For context:

- React: ~10:1

- Next.js: ~16:1

A low ratio means people are grabbing the code, not just bookmarking it. OpenClaw’s is unusually low. Whether that’s because the tool rewards customization, because the ecosystem hasn’t consolidated around plugins yet, or because people want to run it privately and not tell anyone — probably all three.

And now that the creator is inside OpenAI and the project is headed for a foundation? That cl-core-mit-snapshot fork starts looking less paranoid and more prescient.

The timing

Peter Steinberger announced yesterday that he’s joining OpenAI. Sam Altman said on X that OpenClaw will “live in a foundation as an open source project that OpenAI will continue to support.”

So let me get this straight: The tool was originally called ClawdBot — you can guess which model it was built for. The tool’s creator just joined OpenAI. The tool will live in a foundation that OpenAI sponsors. And 34,600 people have already forked the code, 81% of whom will never touch it again.

If you’re keeping score at home, a developer built a personal agent, originally called it ClawdBot (no points for guessing the model), made it go viral, got hired by OpenAI, and the project is now an “independent foundation” that OpenAI “supports.” This is like a Ford engineer building the best car on the market using Toyota engines, then getting hired by GM to “drive the next generation of personal vehicles.”

The claw is the law, apparently. Just not any particular company’s law.

What I couldn’t measure

Two of my three original questions remain unanswered:

- ✅ Fork creation over time — covered, with the API gap caveat

- ❌ Forks with independent commits — sampled 100, can’t do all 34,600 without days of API scraping

- ❌ Forks that sent PRs back to main — same problem, worse

A more rigorous analysis would use GitHub’s BigQuery dataset. This was a 30-minute investigation, not a thesis. But the 30 minutes told a story.

The real question

34,600 forks sounds massive. It is massive. But the real number is somewhere between 6,500 (19% active) and 700 (2% with intent). Still impressive, and still accelerating.

The open-source AI agent space is in its “everybody forks, nobody contributes back” phase. That’s fine — it’s how platforms grow. The interesting question isn’t how many forks exist today. It’s how many of them will still have commits six months from now, when the foundation has governance, when OpenAI’s priorities inevitably diverge from the community’s, and when the next shiny thing comes along.

History suggests: about 2%. But those 2% will be the ones that matter.

Data pulled from the GitHub REST API v3 on February 15–16, 2026. Fork listing capped at 400 per sort direction; findings are based on sampled bookends, not the full dataset.